Introduction

In the space of roughly 30 years or so, the prison population in America expanded exponentially, from 300,000 to over 2 million individuals (1). This increase was most pronounced in the 1980’s and 90’s during the early years of the “War on Drugs.”

After outlining some basic statistics from Minnesota and the nation at large, this article will draw particular attention to mandatory minimums, which have come under intense scrutiny in recent years on account of the repercussions of said policies. Due to a noted correlation between incarceration rates and mandatory minimums, many policy experts have levied for a significant overhaul to their usage and this has elucidated why “Advocacy and changes at each level [of the criminal justice system] are critical for ending mass incarceration” (2).

Distinguishing the State & Federal Correctional Systems

The responsibilities of the criminal justice system vary at state, federal and local levels. This is because “The judicial system divides responsibilities for prosecution and incarceration at local, state, and federal levels.” Sentencing and incarceration aggregates also tend to fluctuate across jurisdictions and between states. As one might expect, this can be attributed to an entire assortment of factors, including prosecutorial and/or judicial discretion. Similarly, because legislation and enforcement occur through both state and federal institutions, there is a range of variance around the nation. Take mandatory minimums for example, which standardize and specify minimum sentencing requirements for disparate kinds of crimes such as drug offenses (3). Federal mandatory minimums prescribe precise sentences for specific violations, while a state may or may not have their own mandatory minimums. Typically, “Mandatory Minimums” involve a drug or firearm offense. In all such criminal cases, the judge does not have the power or ability to reduce or modify sentencing that involves a mandatory minimum related crime. The consequences of this policy at state and federal levels will be highlighted briefly at a later point in this article.

Incarceration Statistics in Minnesota

Minnesota has a relatively small rate of adult incarceration in comparison to the general population. In 2018, for example, about 15,900 adults were jailed or imprisoned in the state at a rate of 370 per 100,000 (4). In fact, Minnesota ranked 47th when collated with other states, generally holding one of the lowest rates of incarceration. Consider how Minnesota compares with our neighboring state, Wisconsin, where the general population is roughly equivalent to ours. In the same year, Wisconsin incarcerated 36,700 adults at a rate of 810 per 100,000 (5). In spite of these positive figures, it has been noted that over the past decade and a half, Minnesota has also experienced one of the more markedly significant increases in incarceration in the United States (6).

Disparities in Incarceration

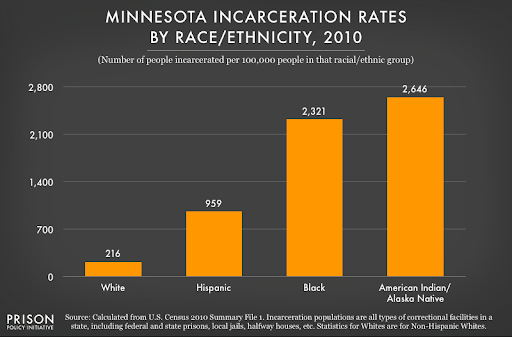

This is particularly relevant in light of Minnesota’s very high racial disparities. According to data that the “Sentencing Project” has collected, Minnesota is one of five states where the rate of incarceration among African-American and Caucasian adults is at least 10 to 1 (7). In fact, the existing disparities between white and black Minnesotans in other areas such as home ownership, education and median household income, are some of the worst in the nation (8). This establishes Minnesota as the state with the 4th highest disparity between blacks and whites. Similar discrepancies exist between Native Americans, Hispanics and Caucasians in the Minnesota correctional system as well. Numbers from three different racial demographics published by the Bureau of Justice in 2013 show the widening gaps between these groups, most notably in states like Minnesota. For every hundred-thousand people, whites are incarcerated at 111 per 100,000, whereas African-Americans were at 1219 and Hispanics 287 (9). The Vera Institute for Justice has provided some helpful charts which track these statistics (10). The following graphic from the Prison Policy Institute helps illustrate the stunning degrees of disparity manifesting within the Minnesota correctional system.

See footnote #11

Organizations like the Sentencing Project and others have observed that the contributing factors to racial disparities are often complex and multi-faceted. Nonetheless, they remain a concern worth drawing attention to in the hopes of greater mitigation (12). In general, state incarceration rates are higher than federal and so “it is critical to understand the variation in racial and ethnic composition across states, and the policies and the day-to-day practices that contribute to this variance” (13).

Policy Concerns

For many years, policy advocates have labored to draw attention to the serious drawbacks of sentencing laws like mandatory minimums (14). Some advocate for a total repeal of mandatory minimums, while others argue that certain components should be reformed and others completely removed. Bipartisan support for changes to mandatory minimums at both the federal and state level has been growing for some time now. Let us touch briefly now on some of the concerns that citizens and lawmakers have been voicing for some time (15).

Because of the rapid increase in incarcerated individuals in America over the past four decades, many have begun reassessing the specific policies that likely bear a degree of responsibility for the surge in the American prison population. While carrying the basic advantage of uniformity, which can prevent bias from clouding the potential rulings of a judge and the jury, mandatory minimums tend to create a “one size fits all” approach to sentencing. This prevents a court from considering an individual’s unique situation (16). As a result, the particulars of an individual’s history (such as addiction) are rendered irrelevant to the case. Only the offense itself is deemed pertinent to sentencing. This disallows valuable information from being brought into the case. It also reduces a person with a distinct past and identity to the lowest denominator of their individual history. Personhood is erased and replaced with an identity as a felon, an addict etc. Critics have insisted that mandatory minimums do little to reduce rates of drug possession and lead primarily to unnecessarily long prison sentences which exacerbate the problem of mass incarceration. The correlation then, between the amount of drugs possessed and the length of a sentence, is always dramatic. In the case of LSD, an individual may face a five year increase in prison time due to the possession of a “fraction of a gram” more (17).

While mandatory minimums can eliminate “sentencing disparity,” among other things, the relationship between policy and racial disparity underscores the necessity for reform. Before concluding, let us examine the effects of mandatory minimum drug sentencing and racial disparity.

Policy & Disparity

Policies like mandatory minimums can and do have the tendency to disproportionately affect racial minorities. Judges cannot override or modify mandatory minimums. And while prosecutors have some discretion and the ability to choose which charges to pursue, a study from the Yale Law Journal has made the case that a prosecution is ‘twice as likely to charge a black offender with a mandatory minimum drug sentence as a white individual who has committed the same offense’ (19). So while this phenomena occurs with all manner of mandatory minimums, it has grown most notable when it comes to drug offenses, which also often lead to rather harsh sentencing for negligible levels of possession (or various minor offenses). In short, the punishment is almost always disproportionate. Racial disparity in drug sentencing has been most infamously prominent in the case of cocaine and the rates of incarceration for crack vs powder cocaine. For many years, sentencing occurred at a rate of 100 to 1 for crack and powder cocaine respectively. In the last decade that number has been reduced and now stands at 18 to 1.

Due to socioeconomic factors, possession of crack vs powder cocaine often manifests across different racial demographics, with a higher usage of powdered cocaine among Caucasians and a higher usage of crack cocaine among African-Americans. Despite reforms, disparities have remained largely unremediated and where changes have been made, there has not been retroactive action to reverse sentences for those currently serving time.

For decades, “someone convicted of possessing one gram of crack would receive a sentence 100 times longer than someone possessing one gram of powder cocaine” (20). This occurred (and still occurs at the federal level) in spite of the preponderance of evidence that demonstrates that there is essentially no real chemical difference between crack and powder cocaine (21). As such, the perception of crack cocaine has contributed to an ongoing racial disparity in U.S. drug legislation and enforcement. It is believed by many experts that, “Crack cocaine’s lower price, ease of production and manner distribution was thought to have made it more accessible in poor, urban communities than powder cocaine” (22).

Progress & Potential Areas for Criminal Justice Reform

Many states have repealed or reformed mandatory minimums in the past decade, particularly for “non-violent” related offenses (23). In 2010, the “Fair Sentencing Act” was passed which helped reduce (but not eliminate) the cocaine sentencing disparity while abolishing the five-year federal mandatory minimum for possession of five grams of cocaine (24). The “Justice Safety Valve Act” of 2013 has provided the ability for judges to give exemptions to mandatory sentencing among other things. The “First Step Act” passed in 2018 initiated various provisions that will also help alleviate sentencing discrepancies by reducing mandatory sentence lengths, expanding safety valves and eliminating certain charge “stacking.”

In 2016, Minnesota saw the implementation of MN Senate bill 3481, “which placed greater emphasis on rehabilitation and eliminated mandatory minimums for low-level drug cases” (25). Although not necessarily directly correlated, Minnesota has seen some shifts in the number of individuals incarcerated for drug vs violent offenses, which is an additional positive change. Various reforms and legislative action in 2016 contributed to a much needed “overhaul” in drug related policy and enforcement (26). As a result, greater distinction was created between sentencing for drug addicts vs drug dealers:

All of these changes – increased quantity thresholds, stricter mandatory minimum sentences, and expanded eligibility for statutory stays of adjudication all seek to target drug kingpins over addicts to keep serious offenders off the streets longer while ensuring that fewer addicts are sent to jail or prison (27).

Conclusion:

The criminal justice system in the United States should funnel more resources towards rehabilitation rather than penalization, especially in cases involving drug addiction and mental illness. The American Conservative Union Foundation researches and champions justice reform and has noted that the United States justice system should commit itself to the expansion of courts that “specialize in dealing with specific populations (such as veterans, people with mental illness, and those with drug and alcohol addictions)” (28). Such a principle should be the benchmark, even the prerequisite for a functional and healthy correctional system, one which advocates for rehabilitation and the reduction of recidivism.

This sampling of key topical points and data is demonstrative of the moderate progress made in criminal justice policy, particularly in relation to mandatory minimums. As noted earlier however, states like Minnesota still have significant progress to make, particularly in redressing racial inequity and criminal justice reform. Positive movement with mandatory minimums has been made around the country and in Minnesota. A reduction in the severity of mandatory minimums has been made (particularly those related to drug offenses), but many are still serving time for policies that have since been repealed or reformed. Consider reaching out to your congressional representative or senator to call for retroactive changes to federal mandatory minimums so that those still serving lengthy sentences for amended policies can have a chance to reenter society sooner.

In future articles, we will explore other areas of criminal justice which demand similar explorations. These will be featured on our new blog tab, “Theological Trails,” which is set to be launched in February. Theological Trails will be dedicated specifically to issues related to the correctional and criminal justice system, but also to issues that affect the prosperity, safety and wellbeing of our communities. Most importantly, such subjects will ultimately be viewed and discussed through the lens of Christian theology rather than a purely secular perspective. Be on the lookout for that!

If you’d like to get involved in policy reform, legislative advocacy or other similar endeavors, consider looking into some of the following organizations! Consider reading and signing the “Prayer and Action Justice Initiative,” a biblically oriented campaign seeking to bring the Church together in a non-partisan fashion by calling us back to the biblical mandate to seek justice for all and to live righteously. Furthermore, PAJI exhorts us to participate and to join in prayer with members from diverse denominational and ethnic backgrounds while simultaneously pursuing action through “personal and institutional resources,” in order to “advocate for more just policies” (29). Other organizations like FAMM and Prison Fellowship are also worth exploring.

Thank you for reading!

In Christ,

-Josiah Callaghan

Footnotes:

- See Marc Mauer, Race to Incarcerate, (New York City, NY, The New Press, 2006), 33.

- See https://www.fcnl.org/updates/2016-09/state-and-federal-responsibilities-criminal-justice. Mass incarceration refers to the drastic increase in the federal and state prison populations at rates which are strikingly and troublingly unique to the United States and in turn engenders and exacerbates racial inequalities.

- This can include, but is not limited to, the sale or possession of illegal narcotics such as cocaine or methamphetamines.

- See https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus1718.pdf page 11.

- Ibid. Page 12.

- See https://conservativejusticereform.org/state/minnesota/

- Ashley Nellis, The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons,” Key Findings. See the following article: https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/

- See pgs. 5-16 from the following study https://files.epi.org/uploads/Race-in-the-Midwest-FINAL-Interactive-1.pdf

- Ibid., Table 1.

- See https://www.vera.org/downloads/pdfdownloads/state-incarceration-trends-minnesota.pdf

- See https://www.prisonpolicy.org/profiles/MN.html

- Ibid. “The Scale of Disparity,” and “The Drivers of Disparity.”

- A. Nellis, “The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons,” Overview.

- “Three Strikes” laws are a form of mandatory minimums.

- Consider the following article for an evaluation of the pros and cons of mandatory minimums. See https://www.heritage.org/crime-and-justice/report/reconsidering-mandatory-minimum-sentences-the-arguments-and-against

- See https://famm.org/wp-content/uploads/FS-MMs-in-a-Nutshell.pdf

- https://www.heritage.org/crime-and-justice/report/reconsidering-mandatory-minimum-sentences-the-arguments-and-against

- Ibid.

- See https://drugpolicy.org/resource/drug-war-mass-incarceration-and-race-englishspanish and Sonja B Starr and Marit Rehavi, “Mandatory Sentencing and Racial Disparity: Assessing the Role of Prosecutors and the Effects of Booker,” Yale Law Journal 123, no. 1 (2013).

- See https://www.heritage.org/crime-and-justice/report/reconsidering-mandatory-minimum-sentences-the-arguments-and-against

- See https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/why-do-we-still-punish-crack-and-powder-cocaine-offenses-differently/ar-BB1ecML7

- See https://www.criminaldefenselawyer.com/resources/crack-vrs-powder-cocaine-one-drug-two-penalties.htm

- https://justicepolicy.org/research/proposition-36-five-years-later/

- https://www.criminaldefenselawyer.com/resources/crack-vrs-powder-cocaine-one-drug-two-penalties.htm

- See https://conservativejusticereform.org/state/minnesota/

- See https://mn.gov/sentencing-guidelines/training/drug-modifications-2016/2016-drug-reform-act/

- See https://www.dwiminneapolislawyer.com/minnesota-new-drug-laws/

- See https://conservativejusticereform.org/

- See https://www.prayerandactioncoalition.org